For nearly two decades, Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, and Novak Djokovic didn’t just dominate men’s tennis — they fundamentally reshaped how greatness is measured. Their unprecedented achievements distorted historical benchmarks, raised expectations for future generations, and changed how fans, media, and players perceive success. Looking back at the first quarter of the 21st century, it becomes clear just how radically the Big Three altered the sport’s standards.

What Does “Greatness” Really Mean in Tennis?

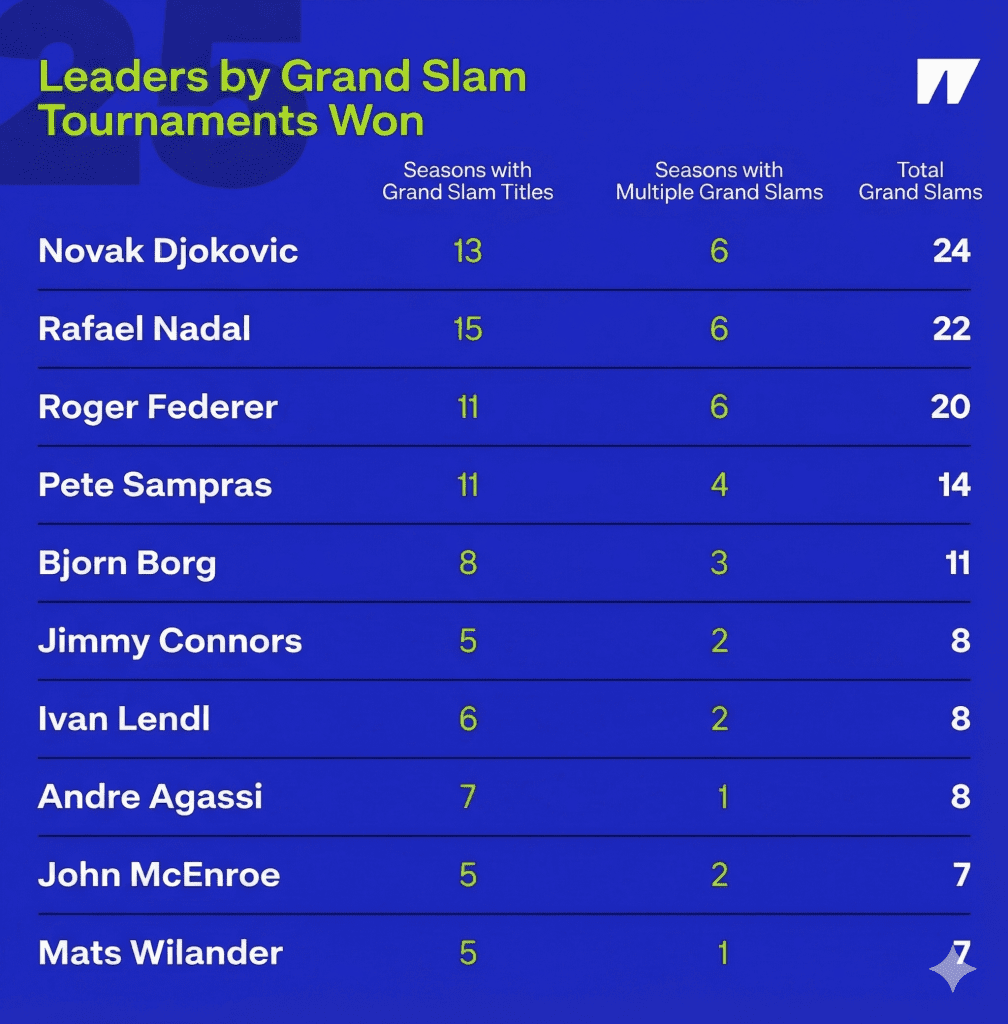

Twenty. Twenty-two. Twenty-four.

That is how many Grand Slam titles Federer, Nadal, and Djokovic won respectively. By a wide margin, they sit atop the men’s all-time list.

Before them, Pete Sampras held the benchmark with 14 major titles — a record that once seemed untouchable. Federer surpassed it first, then Nadal, and finally Djokovic, each becoming the most decorated Grand Slam champion in history in turn.

But this raises a fundamental question: who decided that Grand Slam titles should be the primary measure of greatness?

Grand Slams Were Not Always the Ultimate Metric

For much of tennis history, they weren’t.

Before 1968, professional players — often the very best in the world — were barred from competing in Grand Slam tournaments. Any historical comparison across eras must account for this structural limitation.

Even after the Open Era began, the four majors were not treated equally. Until the 1990s, the Australian Open was frequently skipped by elite players. Björn Borg played it just once. Jimmy Connors only twice. In the 1970s, Connors openly boycotted Roland Garros for years. Wimbledon, meanwhile, was considered almost irrelevant by many Spanish players, who viewed grass as unsuitable for “real” tennis.

The idea that Grand Slams were sacred events — tournaments that could never be skipped — only solidified in the early 2000s. Likewise, the obsession with total Grand Slam count is a relatively modern phenomenon.

The Sampras Effect and the Birth of Modern Records

Pete Sampras changed the narrative.

By the late 1990s, American media increasingly framed Sampras’ career around historical records: Grand Slam totals and weeks at world No. 1. These became the defining metrics of greatness.

Before Sampras, Roy Emerson held the men’s record with 12 majors, yet few spoke about “breaking Emerson’s record.” Björn Borg finished his career with 11 majors — despite rarely playing in Australia — and showed little interest in chasing numerical milestones. He openly stated he would only travel to Melbourne if he had a chance at a calendar Grand Slam.

That mindset vanished with Sampras — and completely disappeared with the Big Three.

The Big Three: Dominance in a Fully Formed Era

Federer, Nadal, and Djokovic were the first truly great players to compete after modern criteria for greatness were already established. And what they did within those criteria was unprecedented.

From 2005 — Djokovic’s first full season on tour — through early 2023, the Big Three won 59 of 71 Grand Slam titles, or 83.1% of all majors during that period.

This level of dominance has no historical parallel.

How the Big Three Warped Perspective

Against this backdrop, achievements that once defined greatness now appear diminished.

Andre Agassi won eight Grand Slam titles and became world No. 1. In the Big Three era, that résumé feels modest. Sampras’ 14 majors — once mythical — look ordinary next to Nadal’s haul at Roland Garros alone.

Players like Daniil Medvedev (one Grand Slam, former world No. 1) or Andy Roddick (one Grand Slam, former world No. 1) are often framed as underachievers — despite careers that would have defined entire generations in previous eras.

Even Agassi, the first man to complete a Golden Career Grand Slam, can feel “lesser” when seen standing beside Djokovic. That distortion of perception is one of the Big Three’s most profound legacies.

Expectations for the Future Have Shifted

The effect extends to the next generation.

Carlos Alcaraz and Jannik Sinner are producing historically elite results — multiple Grand Slams per season, consistent finals, massive ranking gaps over the field. Yet the dominant question is not how great they already are, but whether they can catch the Big Three.

Before Federer, Nadal, and Djokovic, only five men in tennis history won double-digit Grand Slam titles. In the Open Era, only two did. Now, anything less feels insufficient.

That is the new standard — fair or not.

Why Women’s Tennis Is Viewed Differently

Interestingly, this phenomenon is far less pronounced on the women’s side.

Serena Williams won 23 Grand Slam titles, yet new champions are not routinely measured against her in the same way. Serena, for many reasons — cultural, physical, stylistic — was never mythologized as a universal benchmark in the same manner.

Some fans unfairly dismiss women’s tennis as “easier,” which diminishes how dominance is perceived. This view is deeply flawed, but it helps explain why Serena’s records did not distort expectations to the same extent.

Men’s tennis, by contrast, is often seen as the sport’s ultimate proving ground — and thus its records are treated as sacred.

The Normalization of Two-Decade Excellence

Federer, Nadal, and Djokovic won their first Grand Slams between ages 19 and 21 — and their last at 37. Nearly 20 consecutive years of elite success.

In tennis terms, this is an anomaly.

Most players peak for five years. Great players might sustain excellence for eight to ten. The Big Three operated at or near their peak for nearly double that.

As a result, modern expectations now demand that top players:

- Remain elite for exceptionally long periods

- Continue winning major titles well into their 30s

Anything less is often viewed as failure — an unreasonable standard shaped by extraordinary outliers.

A Distorted View of Player Development

The Big Three also simplified how fans and media perceive improvement:

- Identify a weakness

- Fix it

- Start winning

That worked for Federer, Nadal, and Djokovic — but it does not work universally.

Federer reinvented his backhand at 35. Nadal became an elite net player after already winning countless titles. Djokovic turned marginal gains into an art form.

Most players face real physical, technical, and psychological limitations. Andrey Rublev will never become a serve-and-volley specialist. Stefanos Tsitsipas has worked for years on his backhand slice and return — with limited progress. Not due to effort, but natural constraints.

Yet the Big Three made exceptional growth appear normal.

The Alcaraz–Sinner Paradox

This is why the progress of Alcaraz and Sinner is often underappreciated.

Sinner identified weaknesses in his serve and variety after the US Open — and addressed them within months, using them to defeat Alcaraz at the ATP Finals. Such transformation usually takes years.

Alcaraz, meanwhile, achieved something equally rare: he mastered his temperament, becoming stable and deliberate across an entire season. Many players manage that for a tournament or two. Sustaining it is extraordinary.

Yet today, such progress is viewed as the minimum requirement for historical greatness — a standard that barely existed 25 years ago.

The Lasting Impact of the Big Three

That is the true legacy of Federer, Nadal, and Djokovic.

They did not just win titles. They shifted the baseline of what success looks like, distorted historical comparisons, and raised expectations to unprecedented levels.

Their achievements may never be replicated. In time, they may be remembered like Wilt Chamberlain’s 100-point game — untouchable, almost mythical.

But for now, every champion lives in their shadow.

For more in-depth analysis, historical perspectives, and daily updates from the world of professional tennis, explore our tennis news section, where we cover the latest stories, trends, and debates shaping the sport.